(Click on images for larger view)

By Robert Irwin

The idea to place a commemorative plaque on a remote mountain top in Labrador first hit me in the summer of 2009. My friend Philip Schubert and I had just finished exploring some sections of the ill-fated, 1903, Hubbard expedition. In earlier years Philip and I had retraced portions of the route independently but this was our first joint venture.

The Lure Of The Labrador Wild by Dillon Wallace, one of the original explorers, has been a valuable reference source.

Philip who lives in Kanata, Ont. is an authority on Leonidas Hubbard’s epic journey through what was at the time an uncharted part of North America. Poor weather combined with a tight schedule ended our 2009 exploration prematurely but we promised each other that we would return to the area and climb the 750 ft. land mass Wallace referred to as Mount Hubbard. I haven’t noticed that name on any modern maps but given its historical importance maybe it should be. You’ll find it here: Latitude: 53.99091 Longitude:-63.32617

Mount Hubbard rises out of Windbound Lake. Today Windbound Lake, Michkamau and an assortment of other lakes and rivers, are part of the Smallwood Reservoir, a 6,527 km² an area flooded in the 1970s as part of the Churchill Falls hydroelectric project. For my farming colleagues that’s: 1,612,800 acres!

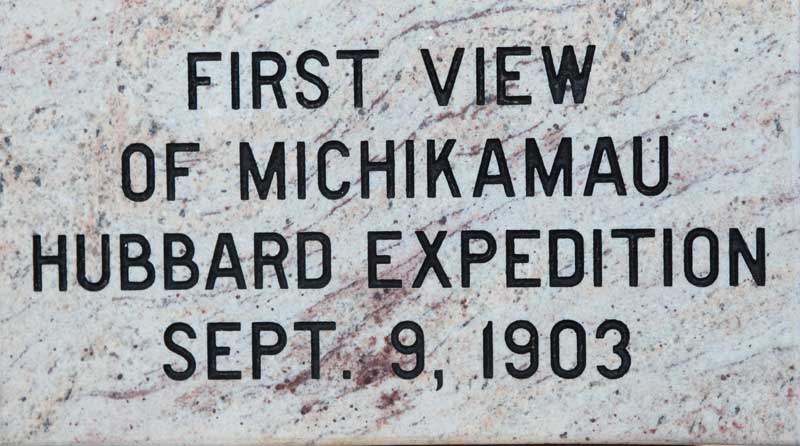

Without any maps to guide them Leonidas Hubbard Jr. and his two companions, Dillon Wallace and George Elson, were forced to climb mountains in an effort to plot their course. From the top of this particular mountain, Hubbard knew he had finally found Michikamau, the vast inland sea he had been searching for, relying mainly on natives’ vague descriptions passed down from their elders.

This mountain was the furthest point Hubbard reached. His remaining days were spent wind bound nearby for a week (hence the name of the lake) and subsequently in full retreat, with winter closing in and his food supply exhausted.

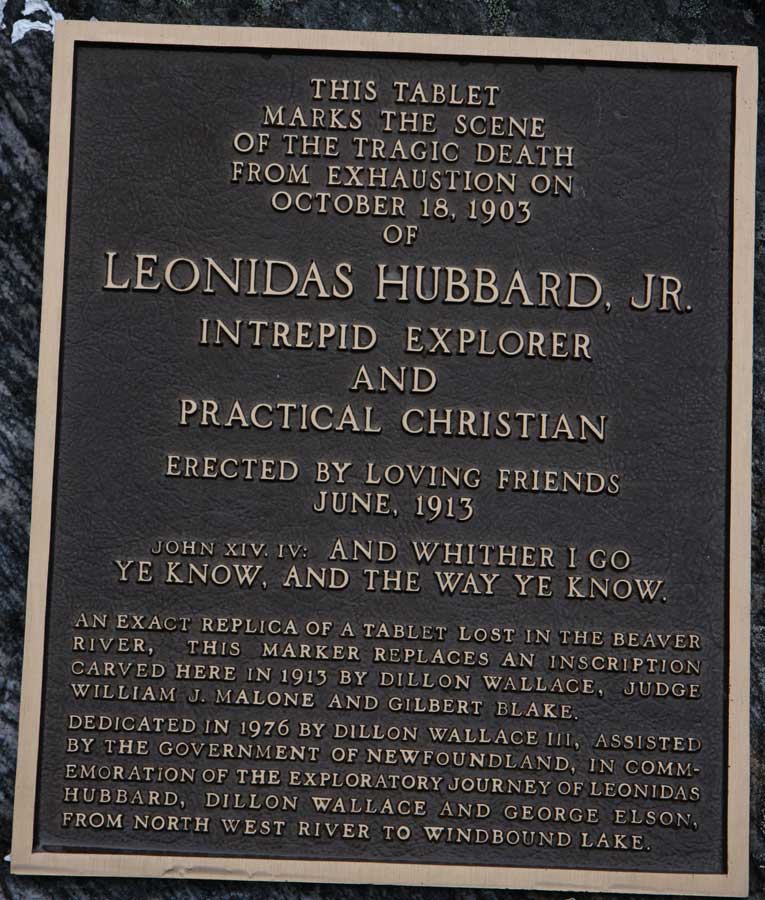

Like most canoeists I try to leave no trace of my presence when I pass through an area but this situation seemed to cry out for an exception. On earlier occasions Philip and I had visited a historical plaque, on a large rock beside the Susan Brook, where Hubbard died, October 18, 1903.

That marker is relatively inaccessible. Only a handful of canoeists and hikers have been willing to spend the days needed to penetrate the miles of dense alders, Black Spruce and mountains protecting the site. Most who have placed messages in the canisters there came by helicopter.

Philip is one of the exceptions and you can read about that amazing accomplishment here: http://magma.ca/~philip18/Hubbard-Rock.html

The Smallwood Reservoir is “big water,” for canoeists: meaning wind and waves instead of the rapids and portages we deal with on rivers. It’s also very cold water which poses the risk of hypothermia in the event of an upset.

In the summer of 2010, I contacted Michel and Andre Martel of Martel & Fils Sons Inc. in Vankleek Hill, Ont. They created a granite plaque with an inscription I provided. Despite some surprisingly clear images on Google Earth I really couldn’t be certain what would await us on Mount Hubbard. The Martels provided some special epoxy glue in the hopes there would be a suitable rock to attach the plaque to. Assuming we reached the peak and were able to find something to stick the plaque to, we would still have to find a temporary method of holding the plaque in place and we would have to count on dry warm weather for the glue to set over a 12 hour period.

With the 25 pound hunk of granite tied firmly in the bow of my canoe, under the watchful eye of my cousin Reg Rothwell serving as bowman, we set out July 16, 2010 with Philip in his solo canoe. Following a short day's paddle, we camped on an island for the night and were subsequently pinned down by bad weather. We spent the next two days hiding in our tents from the rain.

Our trip ended abruptly when Philip had to be evacuated by helicopter one morning, due to a sudden medical emergency. I was thankful that I was able to get a strong satellite phone signal. The Royal Newfoundland Constabulary rounded up two paramedics and a Bell 407 helicopter generously provided by Nalcor Energy.

Fortunately the pilot was able to handle poor flying conditions and land on a beach at the edge of the island where we were camped. The weather closed in again for another two days as soon as the helicopter left. When the weather improved Reg and I towed Philip’s canoe back to my SUV and we headed for home.

Philip and I resumed our quest July 9, 2011. Philip a lifelong competitive athlete, was in top shape. It turned out that he had developed a Pulmonary Embolism in his lungs during the trip the year before, something that can happen to athletes as they get older. He felt he was in good company when Serena Williams was hit by one this past spring. He is now on blood thinner which makes his blood flow better for the black flies but which should prevent another embolism!

To minimize our risk he had charted a course that would keep us hidden behind islands whenever practical, as protected from the winds and as close to shorelines as possible. Navigating islands is a confusing prospect at the best of times. But in all our research we never did find a perfectly accurate map of the area. And it seems islands in the reservoir come and go, depending on water levels.

The reservoir is surrounded by 88 dikes. We launched from one of them in full view of our mountain goal, then roughly 17 km away.

The safest route appeared to be to the east and south. Anywhere, it seemed, but toward our goal! For the next two days we paddled slowly along rugged rocky shorelines. The weather remained sunny and cool.

A number of times we had to leave the shelter of an island and cross one or two km stretches of open water. Once or twice during those crossings breaking waves rose higher than three feet. Occasionally a surprise gust would hit us from the side. Despite well-designed spray decks on our canoes and our years of experience in such conditions, this was on the edge of our comfort level.

Most of the time we couldn’t see our mountain. It was obscured by the islands we navigated amongst. Finally on our second full day on the water, around 6:00 p.m., after paddling about 35 km, we emerged from around an island and reached the north side of Mount Hubbard. Then we began looking for a place to camp. Ideally it would be a level clearing in amongst the Black Spruce, well-protected from the high winds known to hit the area. Hopefully too it would be situated near a wind-swept area that would allow us to cook and eat while the wind suppressed black fly activity.

We also needed to find a point of access to the mountain top. The west end was clearly too steep to consider without using climbing gear. Both the south and east sides would have involved a lengthy hike through dense bush just to reach the mountain.

Before long we discovered an ideal campsite about halfway along the north shore.

The next morning we walked out behind our tents, hiked through some alders and Black Spruce for a few hundred metres and began the 750 ft ascent of the mountain. Soon we could look back down on our tents.

In a couple of hours we were gazing out at Michkamau, standing on the mountain peak where Leonidas Hubbard and George Elson had stood Sept. 9, 1903.

We took a moment to read Dillon Wallace’s account of that special day:

"AND THERE WAS MICHIKAMAU!"

We camped at dusk on one of these islands, and on Wednesday, September 9th, launched our canoe at daybreak, to resume our journey to Mount Hubbard. We reached its base before ten o’clock. Blueberries grew in abundance on the side of the mountain, which, together with the country near it, had been burned. One of us, it was decided, should remain behind to pick berries, while the others climbed to the summit. I volunteered for the berrypicking, but I shall always regret it was not possible for me to go along.

Before Hubbard and George returned, I had our mixing basin filled with berries, and the kettle half full. The day was clear, crisp and delightful – one of those perfect days when the atmosphere is so pure and transparent that minute objects can be distinguished for miles. On the earth and on the water, not a thing of life was to be seen. The lake, relieved here and there with green island-spots; the low, semi-barren ridges and hills that we had travelled over bounding the lake to the eastward, and a ridge of green hills west of the lake that extended southward from behind Mount Hubbard as far as the eye could reach – all combined to complete a scene of vast and solemn beauty; and I, alone on the mountain side picking blueberries, felt an inexpressible sense of loneliness – felt myself the only thing of life in all that boundless wilderness-world.

From the moment Hubbard and George had left me, I had not seen or heard them. But up the mountain they went through the burnt spruce forest, up for four miles over rocks, up and up to the top; and then to the westernmost side of the peak they went and looked – looked to the west; and there, only a few miles way, lay Michikamau with its ninety-mile expanse of water – the lake we so long had sought for and fought so desperately to reach. It was there, just beyond the ridge I had seen extending to the southward.

Source: The Lure of the Labrador Wild by Dillon Wallace

Pages 145 and 146

Then we spread our gear out around a rock which seemed to be well situated for our plaque.

I cleaned the rock as well as possble. Then Philip and I applied the Martels' glue to the rock and the plaque. Next we bound everything together with the canoeist’s best friend: duct tape. Later, noticing the duct tape was losing its grip in the hot sun, we wrapped a rope around everything for added insurance.

We also installed a sealed piece of ABS pipe in a rock pile beneath the plaque. This canister contains a pencil and notebook. By unscrewing the end of the pipe, those who follow, will be able to record their presence at this special place.

Did our amateur glue job hold? We couldn’t stay on the mountain top for 12 hours while the epoxy dried to find out. The weather at the time was ideal and the rock surface was dry to begin with.

Much later during our drive home we encountered Randy Miller, vice president exploration, Search Minerals Inc., who is working in the general area. Randy very kindly offered to check on our handiwork next time he is flying over the mountain with a helicopter. Once we hear from him we’ll let you know how things turned out. I am very grateful to Randy and his company for their contribution to this project.

It took us about 1.5 hours to reach our tents from the peak. That night Philip plotted a new route home. It was much more direct with roughly the same number and distances of off-shore crossings.

The only excitement came with about 7 km remaining in our trip. At about 5:00 p.m. Sunday evening while crossing a small expanse of open water, we heard a loud roar, looked back over our shoulders to the west and saw what appeared to be the kind of vertical column associated with a microburst. A massive wind and rain storm was coming at us from about 20 km away. These things can produce winds of more than 140 km / hr.

We knew that relative safety lay on a sandy beach, just behind a Black Spruce-covered island, a few hundred metres to our north. With some effort, in what quickly became gale force winds, I narrowly reached the shore.

Philip, who was just a few canoe lengths behind me, was blown towards a small rocky island about 200 feet by 200 feet in size that he was passing on his right when the blast of wind hit. He managed to land and pull his canoe up on boulders and out of reach of the waves, which quickly built to five feet in height. He then had a heart stopping few minutes as he watched my struggle to get into the wind shadow of the wooded island immediately ahead of me and land.

For the next hour and a half we could only watch each other across 100 metres of turbulent water. We couldn’t hear anything above the roar of the storm. Although each of us was thinking we might be spending the night in our respective locations, the winds dropped as quickly as they had arisen. In less than 90 minutes we were on our way again. By 8:30 p.m. we had our tents set up near my SUV and supper was cooking over a small pile of burning driftwood.

Top

|